In electricity, one important form of potential energy exists in the atoms and molecules of some chemicals under special conditions.

Early in the history of electrical science, laboratory physicists found that when metals came into contact with certain chemical solutions, voltages appeared between the pieces of metal. These were the first electrochemical cells.

Lead-Acid Battery

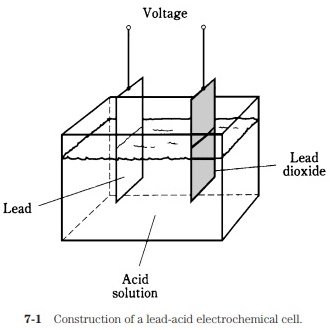

A piece of lead and a piece of lead dioxide immersed in an acid solution (Fig. 7-1) will show a persistent voltage. This can be detected by connecting a galvanometer between the pieces of metal. A resistor of about 1,000 ohms should always be used in series with the galvanometer in experiments of this kind; connecting the galvanometer directly will cause too much current to flow, possibly damaging the galvanometer and causing the acid to "boil."

The chemicals and the metal have an inherent ability to produce a constant exchange of charge carriers. If the galvanometer and resistor are left hooked up between the two pieces of metal for a long time, the current will gradually decrease, and the elec#trodes will become coated. The acid will change, also. The chemical energy, a form of potential energy in the acid, will run out. All of the potential energy in the acid will have been turned into kinetic electrical energy as current in the wire and galvanometer. In turn, this current will have heated the resistor (another form of kinetic energy), and escaped into the air and into space.

Lithium Ion Battery

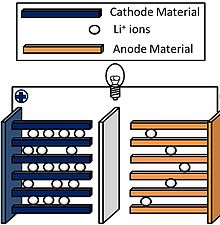

Lithium cells have become popular since the early eighties. There are several variations in the chemical makeup of these cells; they all contain lithium, a light, highly reactive metal. Lithium cells can be made to supply 1.5 V to 3.5 V, depending on the particular chemistry used. These cells, like their silver-oxide cousins, can be stacked to make batteries.

The first applications of lithium batteries was in memory backup for microcomputers. Lithium cells and batteries have superior shelf life, and they can last for years in very-low-current applications such as memory backup or the powering of a digital liquid-crystal-display (LCD) watch or clock. These cells also provide energy capacity per unit volume that is vastly greater than other types of electrochemical cells.

Lithium cells and batteries are used in low-power devices that must operate for a long time without power-source replacement. Heart pacemakers and security systems are two examples of such applications.

About the Author

Stan Gibilisco is one of McGraw-Hill's most prolific and popular authors, specializing in electronics and science topics. His clear, reader-friendly writing style makes his science books accessible to a wide audience, and his background in research makes him an ideal editor for professional references and course materials. He is the author of The Encyclopedia of Electronics; The McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Personal Computing; and several titles in the popular Demystified library of home-schooling and self-teaching books. His published works have won numerous awards. The Encyclopedia of Electronics was chosen a "Best Reference Book of the 1980s" by the American Library Association, which also named his McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Personal Computing a "Best Reference of 1996." Stan Gibilisco maintains a Web site at www.sciencewriter.net.

Quickly and easily learn the hows and whys behind basic electricity, electronics, and communications - at your own pace, in your own home Teach Yourself Electricity and Electronics, Fourth Edition offers easy-to-follow lessons in electricity and electronics fundamentals and applications from a master teacher, with minimal math, plenty of illustrations and practical examples, and test-yourself questions that make learning go more quickly. Great for preparing for amateur and commercial licensing exams, this trusted guide offers uniquely thorough coverage, ranging from dc and ac concepts and circuits to semiconductors and integrated circuits.

The best course - and source - in basic electronics

• Starts with the basics and takes you through advanced applications such as radiolocation and robotics

• Packed with learning-enhancing features: clear illustrations, practical examples, and hundreds of test questions

• Helps you solve current-voltage-resistance-impedance problems and make power calculations

• Teaches simple circuit concepts and techniques for optimizing system efficiency

• Explains the theory behind advanced audio systems and amplifiers for live music

• Referenced by thousands of students and professionals

• Written by an author whose name is synonymous with clarity and practical sense

New to This Edition: Updated to reflect the latest technological advances in:

• Wireless technology

• Computers and the Internet

• Transducers

• Sensors

• Robotics

• Audio systems

• Navigation

• Radiolocation

• Integrated circuits

ReaderRobert L. Young says; "I'm doing course development for a community college. I have evaluated a number of books in order to select one to use as the textbook. The course title is "Basic Electronics and Troubleshooting." This is the book I selected for the course. It has all of the material needed for the course requirements. It has good, understandable illustrations. It includes end of chapter quizzes with answers in the back. The book has far more material than we will be covering in the class, and includes more advanced math than the students will need for this particular course, but I don't see that as a disadvantage. I'll give them reading assignments relevant to the course work, and let them know that the book contains a lot of valuable, additional information for more advanced study. When I say "more advanced study," don't get me wrong; this book isn't a text for a graduate engineering course. It does, however, contain substantially more information than can be covered in a 72 hour Basic Electronics class. All the basics are well-covered and understandable, and the book allows you to keep moving forward from there."

More Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Information:

• Direct Current

• Alternating Current

• How to Calculate Impedance

• All About Microbes

• Introduction to Angles: Acute, Obtuse, Straight, and Right

• Triac

• Circuit Analysis with Thevenin's theorem

• RC Filters

• Average Velocity and Instantaneous Velocity

• Understand E = mc^2