Safely and securely give outside parties access to your network.

Ideally, most local networks are protected from the outside world. If you've ever tried installing a service, such as a web server or a Nextcloud instance at home, then you probably know from first-hand experience that, while the service is easy to reach from inside the network, it's unreachable over the worldwide web.

There are both technical and security reasons for this, but sometimes you want to open access to something within a local network to the outside world. This means you need to be able to route traffic from the internet into your local network - correctly and safely. In this article, I'll explain how.

Local and public IP addresses

The first thing you need to understand is the difference between a local internet protocol (IP) address and a public IP address. Currently, most of the world (still) uses an addressing system called IPv4, which famously has a limited pool of numbers available to assign to networked electronic devices. In fact, there are more networked devices in the world than there are IPv4 addresses, and yet IPv4 continues to function. This is possible because of local addresses.

All local networks in the world use the same address pools. For instance, my home router's local IP address is 192.168.1.1. One of those is probably the same number as your home router, yet when I navigate to 192.168.1.1, I reach my router's login screen and not your router's login screen. That's because your home router actually has two addresses: one public and one local, and the public one shields the local one from being detected by the internet, much less from being confused for someone else's 192.168.1.1.

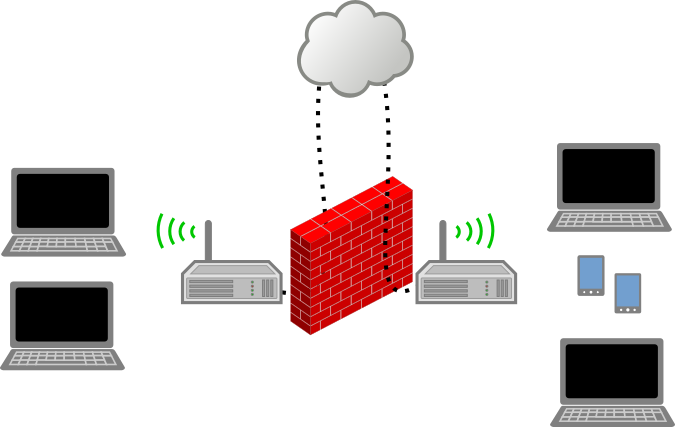

This, in fact, is why the internet is called the internet: it's a "web" of interconnected and otherwise self-contained networks. Each network, whether it's your workplace or your home or your school or a big data center or the "cloud" itself, is a collection of connected hosts that, in turn, communicate with a gateway (usually a router) that manages traffic from the internet and to the local network, as well as out of the local network to the internet.

This means that if you're trying to access a computer on a network that's not the network you're currently attached to, then knowing the local address of that computer does you no good. You need to know the public address of the remote network's gateway. And that's not all. You also need permission to pass through that gateway into the remote network.

Firewalls

Ideally, there are firewalls all around you, even now. You don't see them (hopefully), but they're there. As technology goes, firewalls have a fun name, but they're actually a little boring. A firewall is just a computer service (also called a "daemon"), a subsystem that runs in the background of most electronic devices. There are many daemons running on your computer, including the one listening for mouse or trackpad movements, for instance. A firewall is a daemon programmed to either accept or deny certain kinds of network traffic.

Firewalls are relatively small programs, so they are embedded in most modern devices. They're running on your mobile phone, on your router, and your computer. Firewalls are designed based on network protocols, and it's part of the specification of talking to other computers that a data packet sent over a network must announce specific pieces of information about itself (or be ignored). One thing that network data contains is a port number, which is one of the primary things a firewall uses when accepting or denying traffic.

Websites, for instance, are hosted on web servers. When you want to view a website, your computer sends network data identifying itself as traffic destined for port 80 of the web host. The web server's firewall is programmed to accept incoming traffic destined for port 80, so it accepts your request (and the web server, in turn, sends you the web page in response). However, were you to send (whether by accident or by design) network data destined for port 22 of that web server, you'd likely be denied by the firewall (and possibly banned for some time).

This can be a strange concept to understand because, like IP addresses, ports and firewalls don't really "exist" in the physical world. These are concepts defined in software. You can't open your computer or your router to physically inspect network ports, and you can't look at a number printed on a chip to find your IP address, and you can't douse your firewall in water to put it out. But now that you know these concepts exist, you know the hurdles involved in getting from one computer in one network to another on a different network.

Now it's time to get around those blockades.

Your IP address

I assume you have control over your own network, and you're trying to open your own firewalls and route your own traffic to permit outside traffic into your network. First, you need your local and public IP addresses. To find your local IP address, you can use the ip address command on Linux:

$ ip addr show | grep "inet " inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo inet 192.168.1.6/27 brd 10.1.1.31 scope [...]

In this example, my local IP address is 192.168.1.6. The other address (127.0.0.1) is a special "loopback" address that your computer uses to refer to itself from within itself.

To find your local IP address on macOS, you can use ifconfig:

$ ifconfig | grep "inet " inet 127.0.0.1 netmask 0xff000000 inet 192.168.1.6 netmask 0xffffffe0 [...]

And on Windows, use ipconfig:

$ ipconfig

Get the public IP address of your router at icanhazip.com. On Linux, you can get this from a terminal with the curl command:

$ curl http://icanhazip.com 93.184.216.34

Keep these numbers handy for later.

Directing traffic through a router

The first device that needs to be adjusted is the gateway device. This could be a big, physical server, or it could be a tiny router. Either way, the gateway is almost certainly performing network address translation (NAT), which is the process of accepting traffic and altering the destination IP address.

When you generate network traffic to view an external website, your computer must send that traffic to your local network's gateway because your computer has, essentially, no knowledge of the outside world. As far as your computer knows, the entire internet is just your network router, 192.168.1.1 (or whatever your router's address). So, your computer sends everything to your gateway. It's the gateway's job to look at the traffic and determine where it's actually headed, and then forward that data on to the real internet. When the gateway receives a response, it forwards the incoming data back to your computer.

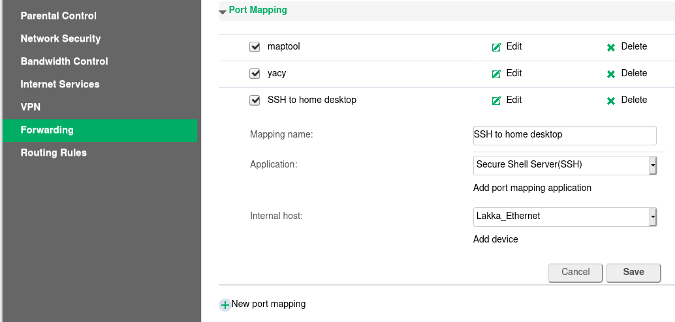

If your gateway is a router, then to expose your computer to the outside world, you must designate a port in your router to represent your computer. This configures your router to accept traffic to a specific port and direct all of that traffic straight to your computer. Depending on the brand of router you use, this process goes by a few different names, including port forwarding or virtual server or sometimes even firewall settings.

Every device is different, so there's no way for me to tell you exactly what you need to click on to adjust your settings. Generally, you access your home router through a web browser. Your router's address is sometimes printed on the bottom of the router, and it begins with either 192.168 or 10.

Navigate to your router's address and log in with the credentials you were provided when you got your internet service. It's often as simple as admin with a numeric password (sometimes, this password is printed on the router, too). If you don't know the login, call your internet provider and ask for details.

In the graphical interface, redirect incoming traffic for one port to a port (the same one is usually easiest) of your computer's local IP address. In this example, I redirect incoming traffic destined for port 22 (used for SSH connections) of my home router to my desktop PC.

You can redirect any port you want. For instance, if you're hosting a website on a spare computer, you can redirect traffic destined for port 80 of your router to port 80 of your website host.

Directing traffic through a server

If your gateway is a physical server, you can direct traffic using firewall-cmd. Using the rich rule option, you can have your server listen for an incoming request at a specific address (your public IP) and specific port (in this example, I use 22, which is the port used for SSH), and then direct that traffic to an IP address and port in the local network (your computer's local address).

$ firewall-cmd --permanent --zone=public \ --add-rich-rule

rule family="ipv4" destination address="93.184.216.34" forward-port port=22 protocol=tcp to-port=22 to-addr=192.168.1.6'

Set your firewall

Most devices have firewalls, so you might find that traffic can't get through to your local computer even after you've forwarded ports and traffic. It's possible that there's a firewall blocking traffic even within your local network. Firewalls are designed to make your computer secure, so resist the urge to deactivate your firewall entirely (except for troubleshooting). Instead, you can selectively allow traffic.

The process of modifying your personal firewall differs according to your operating system. On Linux, there are many services already defined. View the ones available:

$ sudo firewall-cmd --get-services amanda-client amanda-k5-client bacula bacula-client bgp bitcoin bitcoin-rpc ceph cfengine condor-collector ctdb dhcp dhcpv6 dhcpv6-client dns elasticsearch freeipa-ldaps ftp [...] ssh steam-streaming svdrp [...]

If the service you're trying to allow is listed, you can add it to your firewall:

$ sudo firewall-cmd --add-service ssh --permanent

If your service isn't listed, you can add the port you want to open manually:

$ sudo firewall-cmd --add-port 22/tcp --permanent

This step is only about opening a port in your computer so that traffic destined for it on a specific port is accepted. You don't need to redirect traffic because you've already done that at your gateway.

Make the connection

You've set up your gateway and your local network to route traffic for you. Now, when someone outside your network navigates to your public IP address, destined for a specific port, they'll be redirected to your computer on the same port. It's up to you to monitor and safeguard your network, so use your new knowledge with care. Too many open ports can look like invitations to bad actors and bots, so only open what you intend to use. And most of all, have fun!

About the author

Seth KenlonSeth Kenlon - Seth Kenlon is a UNIX geek, free culture advocate, independent multimedia artist, and D&D nerd. He has worked in the film and computing industry, often at the same time. He is one of the maintainers of the Slackware-based multimedia production project Slackermedia.

Opensource.com aspires to publish all content under a Creative Commons license but may not be able to do so in all cases. You are responsible for ensuring that you have the necessary permission to reuse any work on this site. Red Hat and the Red Hat logo are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries.

More Network Troubleshooting and Support Articles:

• Creating a Backup Plan

• What is DevOps?

• Questions to Ask Before Beginning Network Design

• Fiber Optic Cable Tester - What Is It and How to Use?

• Disaster Recovery Planning and Network Services Continuity

• Wireless Network Troubleshooting

• Metro Ethernet Fundamentals for WAN Connectivity

• Five Network Design Considerations

• Structured Network Troubleshooting Methodology Step 4 Establish a Plan of Action to Resolve the Problem and Identify Potential Effects

• Network Design Process - Effective Network Planning and Design